by Randy MacLean, President of WayPoint Analytics

In this article, I’ll share the most effective analytics used by companies to actually control their results. If you have financial or performance responsibility, you’ll likely be using the new measures that follow to get control of your results.

Managers at or near the top of every company have certainly experienced failures in attempts to control the financial measures that please the owners and stakeholders. Traditional financial metrics (like ROI, GMROI, EBITDA, inventory and receivables turns) seem to have a pernicious immunity to our intentions and actions.

The reason for this is that they’re trailing averages, two steps behind the productivity metrics that actually control them. As averages, they’re also nearly useless for actual activity management because they only accurately describe a tiny sliver of the real activity that’s actually near the average. Those averages do not accurately describe the rest of what’s going on, and decisions based on them can be flat wrong for the bulk of the activity in question.

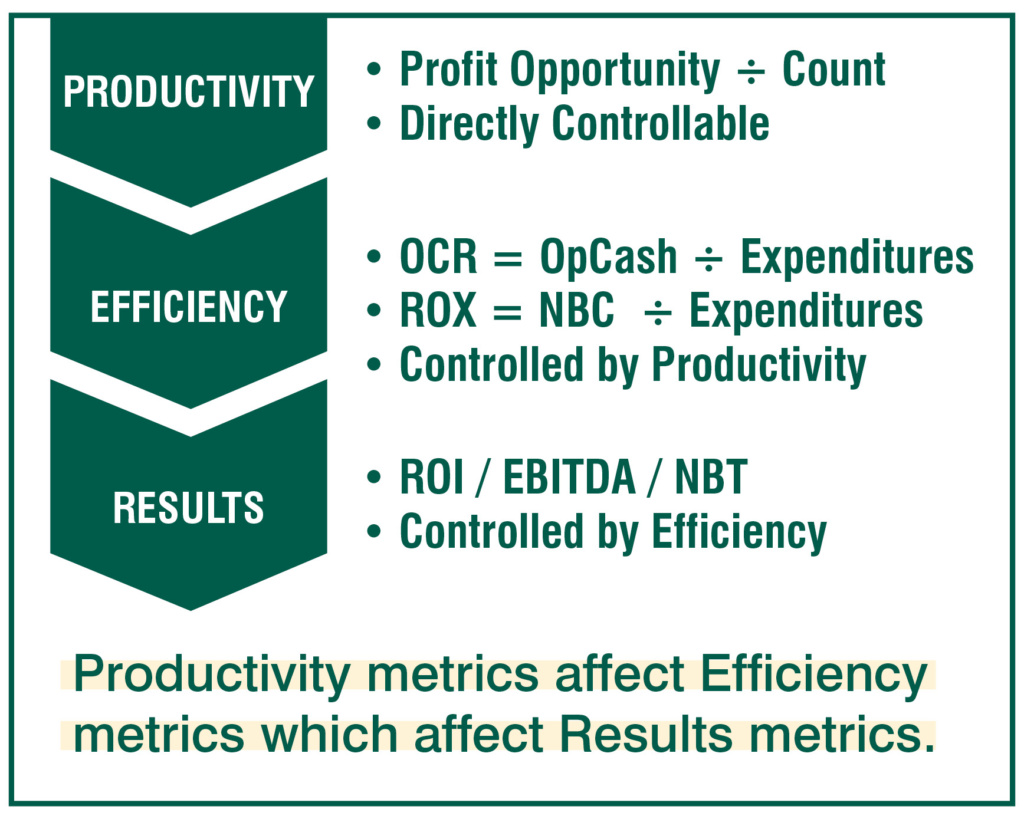

It’s important to realize there’s a natural cascade of effects in the things you can measure. At the beginning are productivity metrics that directly monitor the effectiveness of resource utilization. These directly affect the efficiency of operations which, in turn, influence the financial averages of intense interest to investors and the banks.

In other words, you get control of final results by increasing efficiency, by implementing and managing productivity metrics. There’s simply no other way to change financial performance, and this basic principle puts real control in your hands.

“But Cutting Costs Will Increase Profits, No?”

Well, certainly, but where and how do you cut costs to produce the biggest impact while minimizing unintended consequences?

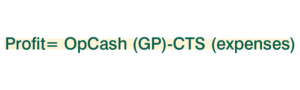

The question is a good one, because the cost-to-serve (CTS) is the true determinant of profitability. Measuring, understanding and managing expenditures in individual sales and customer accounts is really the whole game in controlling profit.

To fully understand what we’re looking at, let me introduce Line-Item Profit Analytics (LIPA).

LIPA is what we do at WayPoint, where our clients use our online system to see the actual costs and profits for every invoice line, product, customer, sales territory, or other identifiable element of their businesses. With this information, clients can see why a 22% margin is a gold mine in one account (where costs are 8.7%) and complete catastrophe in another (where costs are 28%). LIPA has opened an entire new field of analysis, with its own vernacular to describe the dynamics that confer direct control of cash-flow and profits.

Before LIPA, all you could do is use rule-of-thumb concepts (increase inventory turns), or blunt actions (cut headcount by 8%), and hope you got positive results (or any results at all). Unfortunately for many, rule-of-thumb cost-cutting has driven some of the dumbest decisions in business. Remember “New Coke?” Or IBM putting themselves out of the computer business?

LIPA shows where cuts are going to be productive, or be predicably catastrophic for an important account. You make better decisions, and your initiatives tend to produce greater and more positive results.

The Conversion Chain

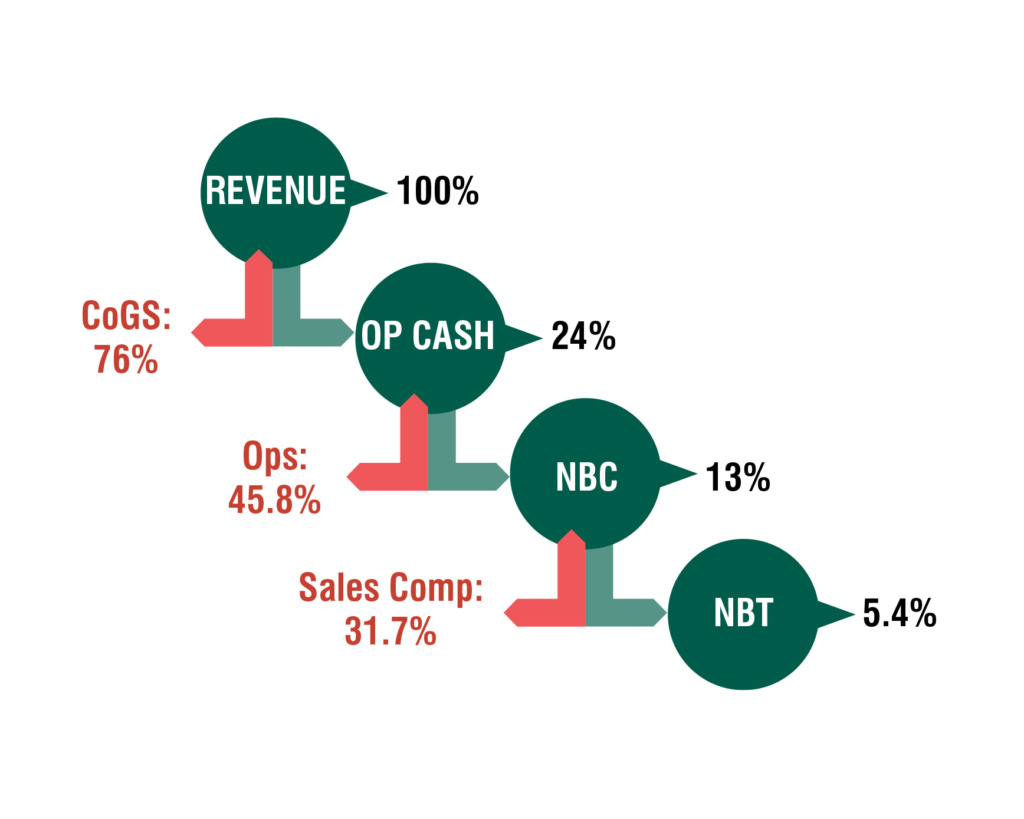

The lynchpin for understanding the financial function of a company is recognition that the company’s very purpose is to convert revenue derived from products and services into profit. Although this seems obvious, people forget all about it while focused on moving more product and trying to raise margins.

Conversion chains, showing how much of original revenue remains at each step (black),

and what portion of remaining value is diverted to pay company costs at each stage (red).

The company’s overall conversion chain is the sum of individual conversion chains in all customer relationships. What a customer buys, and at what price, determines the OpCash (operating cash or our term for Gross Profit) which is the ceiling for profit opportunity. The way the customer buys determines the expenses incurred in serving the account (CTS), and these two factors determine the profit (or loss) of the relationship.

Margin is nearly irrelevant – it’s only a minor contributor to OpCash. (This is heresy, I know.) The core reason for the failure of most profit-improvement initiatives is that they’re almost exclusively focused on margin, so are unresponsive to the critical factor predictive of profit – cost-to-serve. You cannot effectively influence financial results if you do little or nothing that effectively manages the efficiency driven by the costs of the relationship

Efficiency Metrics

Efficiency metrics are the quantification of the effectiveness of activities in your logistics chain. Increasing operational efficiency directly impacts the efficiency in all of your customer conversion chains. (If you move more product value for less cost, a larger proportion of your customer relationships will be profitable.) This magnifies the effectiveness of the sales team, because you’re doing your part to increase customer value, rather than just relying on them to negotiate higher prices to fund operational inefficiencies.

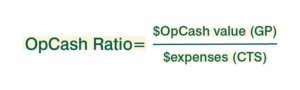

OpCash ratios are the first important type of efficiency metrics because they quantify profit opportunity. That is, they divide OpCash value (the ceiling for potential profit) by expenditures in each step of the logistics chain. Increasing OpCash ratios increases the likelihood of profit being produced by the activity in any particular area.

An example is using OpCash Ratio to evaluate how well money is spent in the distribution centers. One DC has an OpCash Ratio of 13.7:1, meaning it moves $13.70 in product value for each dollar it spends on space and personnel, while another DC’s metric is 15.1:1 – clearly better.

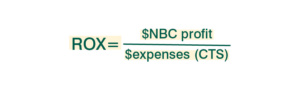

Where OpCash ratios indicate opportunity, ROX (Return on Expenses) quantifies the actual results. For instance, Warehouse ROX is the result of dividing NBC (the LIPA term for operating profit) by the warehouse expenses. It indicates the profit return produced by the expenditures made to support the warehouse.

ROX metrics are the best way to compare the relative effectiveness of various operations (and their managers) between each other. They’re also the best way to quantify improvements made over time.

For instance, a delivery territory that produces a ROX of 2.21 is more valuable and a better profit contributor, than one where ROX is only 1.45. (The first produces $2.21 for every dollar spent, where the latter returns only $1.45.)

Incentives for operational areas tied to ROX will keep managers focused on resource utilization and cost-control at the local level so you don’t have to do it all yourself. Promoting managers based on ROX comparisons will put those with the best track records into positions to mentor others, leveraging their talent in positively influencing company results.

These are great measures to see how important things are being managed and improved, but they’re still not directly manageable. So, how do you get results?

Productivity Metrics

Quantifying the activity-related processes that drive efficiency are the productivity metrics. These marry value to resource utilization, where you get direct control of the entire results chain.

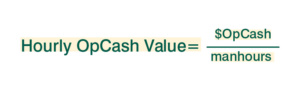

Good productivity measures will divide profit opportunity (OpCash value) into something you can count: like hours, headcount, deliveries, warehouse picks, square footage, etc.

This is where sustained management action controls eventual profits and cash-flow. The need for on-going control and continuous improvement means that managers of operational areas need to be trained on the nature and use of productivity measures, so they can invent and monitor metrics that help them see the impact of good and bad practices, then act to make and measure new improvements on their own.

Productivity measures are mostly used to compare productive performances of individuals, groups of people, infrastructure, delivery vehicles, etc.

For instance, increasing OpCash handled per manpower hour directly suggests that changes (like adding conveyors, optimizing warehouse layout, etc.) which help people handle more value per day will increase efficiency and results.

They’re used throughout operations to evaluate the contribution (or the change in contribution) in each area of the company.

Department heads can be evaluated and incentivized using productivity measures. Since one of the purposes of a management role is to improve performance, productivity measures are the best way of ensuring that improvements are occurring.

For example, you may have one warehouse manager that has delivered a 9.2% increase in OpCash/manhour, as compared to another where the value is unchanged. It’s clear which is more likely to make the company’s profit performance better if promoted to Head of Operations, where the skill is leveraged in mentoring other managers.

At the end, you get control of financial results by widely implementing and managing upstream productivity metrics, then cutting provably unproductive activities and resources. You’ll de-emphasize products and services that serve no strategic purpose and cannot possibly make money. You then either shed costs or re-purpose resources to where they increase profit.

What’s the Take-Away?

The direct path to control and improvement of company results is managing the conversion chain from revenue to profits. The conversion chains for all customers, and for the company as a whole, are directly impacted by operational efficiency, which is controlled by productivity.

Ditch margin programs (except for pricing, where they matter), and implement efficiency measures throughout your logistics chain. Develop productivity metrics and train your people on their importance and use. Add targeted incentives so people become relentless in improving of productivity and, therefore, efficiency. Your financial results will improve automatically.

Very importantly, customer experience and customer loyalty are directly impacted by efficiency – customers are more likely to get the right stuff, at the right time, through a more efficient operation. This drives customer loyalty and, therefore, market-share.

Productivity and efficiency metrics are the direct (and pretty-much, only) path to increased cash-flow and market position, and it improves customer experience and customer success, as well.

Start using these techniques and measures to get in control of your results right now. This month’s financials can be better, and so will those of future periods.

This article is adapted from a section in Profit-Driven Analysis & Practices: The CEO’s Guide to Record Profits by Randy MacLean

(ISBN: 979-8589295375).